Linda Hamalian is a professor of English at William Paterson University. She is the author of A Life of Kenneth Rexroth and coeditor of Solo: Women on Woman Alone.

Request Academic Copy

Please copy the ISBN for submitting review copy form

Description

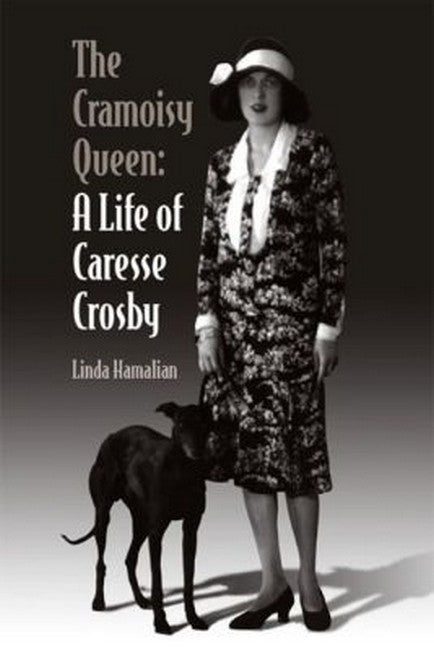

Though she was the bearer of a number of names in her 77 years-Mary Phelps Jacob, "Polly" Peabody, Valerie Marno, "Bunny," the Cramoisy Queen (presumably to suggest the memory of the seventeenth-century French printer/bookseller), even once considering the "too bluestocking" Mary Crosby - it was as Caresse Crosby that this remarkably gifted but tormented woman is remembered. Crosby was the bearer of so many diverse talents that anyone of the following could have brought her various kinds of immortality: inventor (and patent-holder) of the brassiere, co-founder of a distinguished small publishing company that pioneered in producing the works of many of the twentieth century's major literary figures, longtime expatriate, patron of the arts, memoirist, and defiant nonconformist regarding conventional society's values. But although scholars have occasionally discussed Crosby's secure place in modern culture, there has been no full-length biography till now, which makes Linda Hamalian's fine volume unusually welcome. Professor of English at William Paterson University and author of an earlier biography of Kenneth Rexroth, Hamalian is admirably thorough and balanced in this definitive account of a gracious, talented, larger-than-life, deeply haunted woman. Born to a wealthy New York real estate family on April 20, 1892, and descendant variously of a knight of the Crusades, the Allardyce family in the War of the Roses, Colonial governor William Bradford, steamboat inventor Robert Fulton, the first American ambassador to Great Britain, and a noted Union general in the Civil War, Caresse Crosby was raised in true American aristocratic style, even photographed as a child by Charles Dana Gibson. At age 22, she did indeed invent the brassiere, eventually selling the rights to Warner Brothers Corset Co. for a mere $1500. At age 23, she married Dick Peabody, also a socialite, and was soon mother of two small children. But at age 27, she left her family to live with the 21year-old Harry Crosby, energetic non-conformist, having fallen under his spell; lacking "a single marketable skill," she turned to minor film roles and, though disturbed by Harry's drinking, gambling, and general lack of responsibility, she found him irresistible. She was divorced from Peabody in 1922, when she was 30, and married Crosby the same year. Their marriage, however, was a mixture of his infidelities and their new-found talents as printers, which grew into the Black Sun Press in Paris in 1928. Though the Crosbys were not close associates of such other legendary publishers as Sylvia Beach and Robert McAlmon, they knew who and what they wanted to publish (including their own poetry), and in the first three years of their press's existence, they issued well-designed and beautifully produced writings by Ezra Pound, James Joyce, Archibald MacLeish, D.H. Lawrence, Ernest Hemingway, Kay Boyle, and Hart Crane, not too shabby an inaugural list for a new publisher. Despite their professional recognition as avant-garde publishers, though, their indulgence in drugs, alcohol, and a variety of extra-marital lovers dominated their lives. Both, too, were obsessed with death, but Harry, in killing himself (and a lover) in 1929, won that race. Caresse Crosby's life, in many respects really only began with Harry's death, and most of Hamalian's excellent biography focuses on Crosby's remaining decades of life. She was determined to continue the Black Sun Press and to see it succeed by expanding its list to non-affluent readers who wanted "modern masterpieces in English," a list initiated with Hemingway's Torrents of Spring. American publishers such as Random House sought to have Black Sun under their control, and Clifton Fadiman's advice that Crosby publish more saleable authors-including Katherine Anne Porter-left her cold. Her active love-life resulted in two additional ill-fated marriages and various affairs, including one to black actor-boxer Canada Lee, a relationship that helped her explore American racism and prejudice first-hand. She also continued her assaults on the nation's Puritanism, through her publications and even, in the mid-1940s, by a controversial art-show in Washington that led to encounters with the notorious HUAC. Her international instincts, both in publishing and in her personal life, led her to "regard herself as a predecessor of UNESCO," and her series of a half-dozen highly-regarded but exorbitant issues of Portfolio in the late 1940s were among her last Black Sun Press books. Crosby spent the final 20 or so years of her life working with such groups as Women Against War and Citizens of the World. By this time she was living solely in her Italian castle, where she wrote her autobiography, The Passionate Years (1953), which was praised by such figures as T.S. Eliot, Andre Maurois, Jean Cocteau, and Aldous Huxley. Such praise, however, should not be construed as mere author blurbs, for Caresse Crosby had close, long-established professional and personal friendships with an immense array of major literary and artistic figures of the last century, including (in addition to those already mentioned) Max Ernst, Salvador Dali, Anais Nin, Henry Miller, Peggy Guggenheim, Dorothy Parker, William Faulkner, Marcel Proust, William Carlos Williams, Malcolm Cowley, e. e. cummings, Gwendolyn Brooks, David Daiches, Karl Shapiro, Alex Comfort, George Seferis, Walker Evans, and Yves Tanguy. Harry T. Moore (1908-81), prolific author and professor at Southern Illinois University (SIU), and his wife, Beatrice, as well as universal genius Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983), also at SIU, come in for particular emphasis in the latter part of the book; for many years, Moore was greatly responsible for Crosby's academic and financial support, including her appearances at SIU, though he was unable to persuade the university to purchase her Italian castle. She died in Italy on January 24, 1970, at the age of 77. Caresse Crosby was far from being merely the wife of a more famous, more talented man; she was a major influence on much of the most important writing in English produced in the twentieth century, and as such fully warrants this biography that succeeds so assiduously in avoiding mere hyperbole to tell the story of a most unusual, talented, brilliant woman. A reader may notice a few editorial lapses, such as misspelled names, a somewhat inadequate index, and a cumbersome title, but overall these are minor and do not detract from Hamalian's beautifully-written and thoroughly researched biography, a volume certain to help restore Crosby to her rightful place as a major influence on modern literature and art.