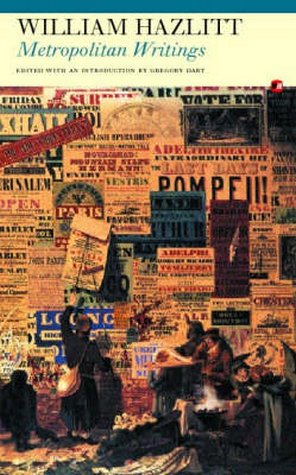

William Hazlitt was born in Maidstone, Kent in 1778, the son of a Unitarian minister. After a short period in America, the family settled in the village of Wem, Shropshire. Hazlitt was educated at the Unitarian college in Hackney from 1793 to 1795, although he decided against the religious life, and began to move in the political and literary circles of Coleridge, Wordsworth, Lamb and Godwin. He wrote philosophy and politics before becoming increasingly involved in literature and journalism. In 1814 he became the Morning Chronicle parliamentary reporter and theatre critic, while also writing essays for journals, including the Edinburgh Review and Leigh Hunt's Examiner. His works on literature include the Characters of Shakespeare's Plays (1817), dedicated to Lamb and admired by Keats; Lectures on the English Poets (1818); The Round Table, in collaboration with Leigh Hunt (1818); and Lectures on the English Comic Writers (1819). His Political Essays were also published in 1819, and Table Talk in 1821-2. In 1825 and 1826 much of his best work was collected in two volumes of essays, The Spirit of the Age and The Plain Speaker. In the Last ten years of his life hazlitt experienced emotional turmoil and poverty, although he continued to publish until his death in 1830.

Description

Nicholas Lezard's Choice: The Incomparable Hazlitt Saturday 12th February, 2005 The Guardian Metropolitan Writings, by William Hazlitt (Fyfield, GBP9.95) A reasonably well-educated friend noticed this book peeping out of my pocket one morning and remarked that it was rather heavy reading for such a time of day, or indeed for any time. I do wish people would stop doing this. Because Hazlitt died 170-odd years ago and is not as famous as Wordsworth or Coleridge, they assume that he cannot be an easy read, or even less of an easy read than W&C, or that to read him is more of a duty than a pleasure. If you want a depressing lesson in contemporary cultural memory, go to any average-sized branch of a chain bookstore and ask for anything by Hazlitt. You will notice that it will take the person at the counter four or five goes to get the spelling right (not that the boss of Fyfield Books has managed to spell my name correctly in 20 years' acquaintance, but that's not important). But the primary reason people still read Hazlitt today, once they can get hold of a copy, is that he is so freshly readable. "Fresh" and "alive" are terms of literary praise that are stale and dead on the page by now, but if they were not, they would be applied unhesitatingly to Hazlitt. The more you read him, the more you will marvel at the way he seems to have written his prose in some kind of ink of immortality, one that preserves the writing's vigour through centuries. Marvelling at the perfect, mechanical precision of a juggler, he looks into his own art and finds it wanting. "The utmost I can pretend to do is to write a description of what this fellow can do. I can write a book: so can many others who have not even learned to spell. What abortions are these Essays! What errors, what ill-pieced transitions, what crooked reasons, what lame conclusions! What little is made out, and that little how ill! Yet they are the best I can do." The self-abasement, you'll have noticed, is rhetorical. By the time you get to the word "ill", you may be mentally patting Hazlitt's hand and saying, don't be so hard on yourself. You may also feel like reassuring him that you are reading these abortions nearly two centuries down the line. Yet that "the best I can do" also pulls us up by reminding us that Hazlitt was a professional, and that he knew what he was doing. The timing of it all is impeccable. But I also suspect that Hazlitt always thought he could do better, and that was what kept his words on their toes for so long. He was the enemy of complacency in himself as well as in others; he certainly fell out with Coleridge and Wordsworth on such grounds, as they abandoned their early attachment to social justice. "Mr C[oleridge] used to say he should like to be a footman to some elderly lady of quality, to carry her prayer-book to church, and place her hassock right for her. There is no doubt that this would have been better, and quite as useful as the life he has led, dancing attendance on Prejudice, but flirting with Paradox in such a way as to cut himself out of the old lady's will." (This is about halfway through his essay "On Footmen", which is included here.) Maybe it's this youthfulness, his refusal to abandon his early ideals of justice and intellectual curiosity, that keep him so evergreen. Nothing was beneath his notice; he turned his frank gaze on everything, and it was, among other things, his cat-can-look-at-a-king approach that made the more high and mighty uncomfortable. Yet this is what makes him so familiar to us now. This edition, which concentrates, though not rigidly, on urban matters, claims to contain "many" essays not hitherto available in paperback. My own copies of two different Penguin editions being at the moment unlocatable, I shall give Fyfield the benefit of the doubt, despite the strong feeling that I have seen quite a few of these pieces before. And at 200 pages, this selection is a little on the ungenerous side. But then it is Hazlitt. Even if there were only one otherwise-unobtainable essay here, you should be rushing out to get this. Go on. Laura Keynes, The Times Literary Supplement, 18th February 2005 "In London", writes Hazlitt in his essay "On Londoners and Country People", "there is a public; and each man is part of it...We comprehend the vast denomination, the People, of which we see a tenth part moving daily before us." It is this spirit of equality and conviviality that Hazlitt celebrates in his writings on metropolitan life, collected here by Gregory Dart. This result is the documentation of an urban consciousness that appears "characteristically modern", as Dart puts it, "in its sense of the city as simultaneously the best and worst place in the world." That sense comes form the personal ambiguity felt by the person brought up in the countryside - in Hazlitt's case, at Wem in Shropshire - with a love and understanding for his environment, who is then compelled to move to the city to find the community necessary to sustain an intellectual life. As anyone who has made that move knows, the sense of belonging neither to one nor the other is a painful and irreconcilable part of making a living through critical observation. The relationship with both environments becomes one of a tourist at best, and the only thing giving London the edge is its ability to offer itself freely to any who will come. Generosity of spirit is indeed the main theme underlying all Hazlitt's writings, though Dart identifies many more in his excellent introduction. In contrast to Wordsworth, Hazlitt gives us the city as facilitator of the imagination, increasing our capacity to enter imaginatively into the life of other individuals that we might feel a bond of sympathy between the individual and society. Dart's success in creating this volume is to challenge the thinking of those who associate Romanticism with nature poetry, and those who feel early nineteenth-century literature is irrelevant to an understanding of our environment today. The Independent Review, Friday 4th February 2005 Fiery, funny, urbane, humane; above all, democratic: the wit and zest of these 18 wonderful essays from the 1820s on London life, fashion and entertainment still grab you like a street-cry. Hazlitt hates cant, pomp and snobbery; he loves taverns, theatres, parties and coffee houses as "the only place for equal society". Several pieces (eg "The Indian Jugglers", on talent versus genius) count as classics of English prose. Hazlitt, the great Cockney Romantic, would loathe such a deadly honour.